THE TOPIC:Social and Personality Development in Childhood

ByRoss Thompson

University of California, Davis

Childhood social and personality development emerges through the interaction of social influences, biological maturation, and the child’s representations of the social world and the self. This interaction is illustrated in a discussion of the influence of significant relationships, the development of social understanding, the growth of personality, and the development of social and emotional competence in childhood.

PDFDownload

Share this URL

Learning Objectives

- Provide specific examples of how the interaction of social experience, biological maturation, and the child’s representations of experience and the self provide the basis for growth in social and personality development.

- Describe the significant contributions of parent–child and peer relationships to the development of social skills and personality in childhood.

- Explain how achievements in social understanding occur in childhood. Moreover, do scientists believe that infants and young children are egocentric?

- Describe the association of temperament with personality development.

- Explain what is “social and emotional competence“ and provide some examples of how it develops in childhood.

Introduction

“How have I become the kind of person I am today?” Every adult ponders this question from time to time. The answers that readily come to mind include the influences of parents, peers, temperament, a moral compass, a strong sense of self, and sometimes critical life experiences such as parental divorce. Social and personality development encompasses these and many other influences on the growth of the person. In addition, it addresses questions that are at the heart of understanding how we develop as unique people. How much are we products of nature or nurture? How enduring are the influences of early experiences? The study of social and personality development offers perspective on these and other issues, often by showing how complex and multifaceted are the influences on developing children, and thus the intricate processes that have made you the person you are today (Thompson, 2006a).

Humans are inherently social creatures. Mostly, we work, play, and live together in groups. [Image: The Daring Librarian, https://goo.gl/LmA2pS, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/Toc0ZF]

Humans are inherently social creatures. Mostly, we work, play, and live together in groups. [Image: The Daring Librarian, https://goo.gl/LmA2pS, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/Toc0ZF]Understanding social and personality development requires looking at children from three perspectives that interact to shape development. The first is the social context in which each child lives, especially the relationships that provide security, guidance, and knowledge. The second is biological maturation that supports developing social and emotional competencies and underlies temperamental individuality. The third is children’s developing representations of themselves and the social world. Social and personality development is best understood as the continuous interaction between these social, biological, and representational aspects of psychological development.

Relationships

This interaction can be observed in the development of the earliest relationships between infants and their parents in the first year. Virtually all infants living in normal circumstances develop strong emotional attachments to those who care for them. Psychologists believe that the development of these attachments is as biologically natural as learning to walk and not simply a byproduct of the parents’ provision of food or warmth. Rather, attachments have evolved in humans because they promote children’s motivation to stay close to those who care for them and, as a consequence, to benefit from the learning, security, guidance, warmth, and affirmation that close relationships provide (Cassidy, 2008).

One of the first and most important relationships is between mothers and infants. The quality of this relationship has an effect on later psychological and social development. [Image: Premnath Thirumalaisamy, https://goo.gl/66BROf, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/FIlc2e]

One of the first and most important relationships is between mothers and infants. The quality of this relationship has an effect on later psychological and social development. [Image: Premnath Thirumalaisamy, https://goo.gl/66BROf, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/FIlc2e]Although nearly all infants develop emotional attachments to their caregivers--parents, relatives, nannies-- their sense of security in those attachments varies. Infants becomesecurelyattached when their parents respond sensitively to them, reinforcing the infants’ confidence that their parents will provide support when needed. Infants becomeinsecurelyattached when care is inconsistent or neglectful; these infants tend to respond avoidantly, resistantly, or in a disorganized manner (Belsky & Pasco Fearon, 2008). Such insecure attachments are not necessarily the result of deliberately bad parenting but are often a byproduct of circumstances. For example, an overworked single mother may find herself overstressed and fatigued at the end of the day, making fully-involved childcare very difficult. In other cases, some parents are simply poorly emotionally equipped to take on the responsibility of caring for a child.

The different behaviors of securely- and insecurely-attached infants can be observed especially when the infant needs the caregiver’s support. To assess the nature of attachment, researchers use a standard laboratory procedure called the “Strange Situation,” which involves brief separations from the caregiver (e.g., mother) (Solomon & George, 2008). In the Strange Situation, the caregiver is instructed to leave the child to play alone in a room for a short time, then return and greet the child while researchers observe the child’s response. Depending on the child’s level of attachment, he or she may reject the parent, cling to the parent, or simply welcome the parent—or, in some instances, react with an agitated combination of responses.

Infants can be securely or insecurely attached with mothers, fathers, and other regular caregivers, and they can differ in their security with different people. Thesecurity of attachmentis an important cornerstone of social and personality development, because infants and young children who are securely attached have been found to develop stronger friendships with peers, more advanced emotional understanding and early conscience development, and more positive self-concepts, compared with insecurely attached children (Thompson, 2008). This is consistent with attachment theory’s premise that experiences of care, resulting in secure or insecure attachments, shape young children’s developing concepts of the self, as well as what people are like, and how to interact with them.

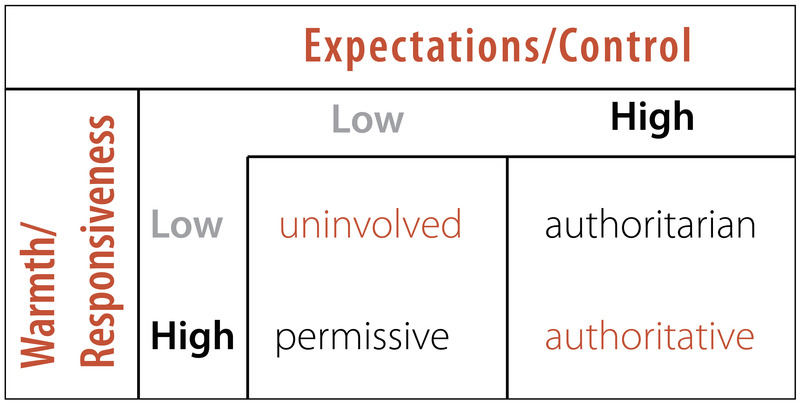

As children mature, parent-child relationships naturally change. Preschool and grade-school children are more capable, have their own preferences, and sometimes refuse or seek to compromise with parental expectations. This can lead to greater parent-child conflict, and how conflict is managed by parents further shapes the quality of parent-child relationships. In general, children develop greater competence and self-confidence when parents have high (but reasonable) expectations for children’s behavior, communicate well with them, are warm and responsive, and use reasoning (rather than coercion) as preferred responses to children’s misbehavior. This kind of parenting style has been described asauthoritative(Baumrind, 2013). Authoritative parents are supportive and show interest in their kids’ activities but are not overbearing and allow them to make constructive mistakes. By contrast, some less-constructive parent-child relationships result from authoritarian, uninvolved, or permissive parenting styles (see Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of Four Parenting Styles

Table 1: Comparison of Four Parenting StylesParental roles in relation to their children change in other ways, too. Parents increasingly become mediators (or gatekeepers) of their children’s involvement with peers and activities outside the family. Their communication and practice of values contributes to children’s academic achievement, moral development, and activity preferences. As children reach adolescence, the parent-child relationship increasingly becomes one of “coregulation,” in which both the parent(s) and the child recognizes the child’s growing competence and autonomy, and together they rebalance authority relations. We often see evidence of this as parents start accommodating their teenage kids’ sense of independence by allowing them to get cars, jobs, attend parties, and stay out later.

Family relationships are significantly affected by conditions outside the home. For instance, theFamily Stress Modeldescribes how financial difficulties are associated with parents’ depressed moods, which in turn lead to marital problems and poor parenting that contributes to poorer child adjustment (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). Within the home, parental marital difficulty or divorce affects more than half the children growing up today in the United States. Divorce is typically associated with economic stresses for children and parents, the renegotiation of parent-child relationships (with one parent typically as primary custodian and the other assuming a visiting relationship), and many other significant adjustments for children. Divorce is often regarded by children as a sad turning point in their lives, although for most it is not associated with long-term problems of adjustment (Emery, 1999).

Peer Relationships

Peer relationships are particularly important for children. They can be supportive but also challenging. Peer rejection may lead to behavioral problems later in life. [Image: Twentyfour Students, https://goo.gl/3IS2gV, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/jSSrcO]

Peer relationships are particularly important for children. They can be supportive but also challenging. Peer rejection may lead to behavioral problems later in life. [Image: Twentyfour Students, https://goo.gl/3IS2gV, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/jSSrcO]Parent-child relationships are not the only significant relationships in a child’s life. Peer relationships are also important. Social interaction with another child who is similar in age, skills, and knowledge provokes the development of many social skills that are valuable for the rest of life (Bukowski, Buhrmester, & Underwood, 2011). In peer relationships, children learn how to initiate and maintain social interactions with other children. They learn skills for managing conflict, such as turn-taking, compromise, and bargaining. Play also involves the mutual, sometimes complex, coordination of goals, actions, and understanding. For example, as infants, children get their first encounter with sharing (of each other’s toys); during pretend play as preschoolers they create narratives together, choose roles, and collaborate to act out their stories; and in primary school, they may join a sports team, learning to work together and support each other emotionally and strategically toward a common goal. Through these experiences, children develop friendships that provide additional sources of security and support to those provided by their parents.

However, peer relationships can be challenging as well as supportive (Rubin, Coplan, Chen, Bowker, & McDonald, 2011). Being accepted by other children is an important source of affirmation and self-esteem, but peer rejection can foreshadow later behavior problems (especially when children are rejected due to aggressive behavior). With increasing age, children confront the challenges of bullying, peer victimization, and managing conformity pressures. Social comparison with peers is an important means by which children evaluate their skills, knowledge, and personal qualities, but it may cause them to feel that they do not measure up well against others. For example, a boy who is not athletic may feel unworthy of his football-playing peers and revert to shy behavior, isolating himself and avoiding conversation. Conversely, an athlete who doesn’t “get” Shakespeare may feel embarrassed and avoid reading altogether. Also, with the approach of adolescence, peer relationships become focused on psychological intimacy, involving personal disclosure, vulnerability, and loyalty (or its betrayal)—which significantly affects a child’s outlook on the world. Each of these aspects of peer relationships requires developing very different social and emotional skills than those that emerge in parent-child relationships. They also illustrate the many ways that peer relationships influence the growth of personality and self-concept.

Social Understanding

As we have seen, children’s experience of relationships at home and the peer group contributes to an expanding repertoire of social and emotional skills and also to broadened social understanding. In these relationships, children develop expectations for specific people (leading, for example, to secure or insecure attachments to parents), understanding of how to interact with adults and peers, and developing self-concept based on how others respond to them. These relationships are also significant forums for emotional development.

Remarkably, young children begin developing social understanding very early in life. Before the end of the first year, infants are aware that other people have perceptions, feelings, and other mental states that affect their behavior, and which are different from the child’s own mental states. This can be readily observed in a process calledsocial referencing, in which an infant looks to the mother’s face when confronted with an unfamiliar person or situation (Feinman, 1992). If the mother looks calm and reassuring, the infant responds positively as if the situation is safe. If the mother looks fearful or distressed, the infant is likely to respond with wariness or distress because the mother’s expression signals danger. In a remarkably insightful manner, therefore, infants show an awareness that even though they are uncertain about the unfamiliar situation, their mother is not, and that by “reading” the emotion in her face, infants can learn about whether the circumstance is safe or dangerous, and how to respond.

Although developmental scientists used to believe that infants are egocentric—that is, focused on their own perceptions and experience—they now realize that the opposite is true. Infants are aware at an early stage that people have different mental states, and this motivates them to try to figure out what others are feeling, intending, wanting, and thinking, and how these mental states affect their behavior. They are beginning, in other words, to develop atheory of mind, and although their understanding of mental states begins very simply, it rapidly expands (Wellman, 2011). For example, if an 18-month-old watches an adult try repeatedly to drop a necklace into a cup but inexplicably fail each time, they will immediately put the necklace into the cup themselves—thus completing what the adult intended, but failed, to do. In doing so, they reveal their awareness of the intentions underlying the adult’s behavior (Meltzoff, 1995). Carefully designed experimental studies show that by late in the preschool years, young children understand that another’s beliefs can be mistaken rather than correct, that memories can affect how you feel, and that one’s emotions can be hidden from others (Wellman, 2011). Social understanding grows significantly as children’s theory of mind develops.

How do these achievements in social understanding occur? One answer is that young children are remarkably sensitive observers of other people, making connections between their emotional expressions, words, and behavior to derive simple inferences about mental states (e.g., concluding, for example, that what Mommy is looking at is in her mind) (Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Kuhl, 2001). This is especially likely to occur in relationships with people whom the child knows well, consistent with the ideas of attachment theory discussed above. Growing language skills give young children words with which to represent these mental states (e.g., “mad,” “wants”) and talk about them with others. Thus in conversation with their parents about everyday experiences, children learn much about people’s mental states from how adults talk about them (“Your sister was sad because she thought Daddy was coming home.”) (Thompson, 2006b). Developing social understanding is, in other words, based on children’s everyday interactions with others and their careful interpretations of what they see and hear. There are also some scientists who believe that infants are biologically prepared to perceive people in a special way, as organisms with an internal mental life, and this facilitates their interpretation of people’s behavior with reference to those mental states (Leslie, 1994).

Personality

Although a child's temperament is partly determined by genetics, environmental influences also contribute to shaping personality. Positive personality development is supported by a "good fit" between a child's natural temperament, environment and experiences. [Image: Thomas Hawk, https://goo.gl/2So40O, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/FIlc2e]

Although a child's temperament is partly determined by genetics, environmental influences also contribute to shaping personality. Positive personality development is supported by a "good fit" between a child's natural temperament, environment and experiences. [Image: Thomas Hawk, https://goo.gl/2So40O, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/FIlc2e]Parents look into the faces of their newborn infants and wonder, “What kind of person will this child will become?” They scrutinize their baby’s preferences, characteristics, and responses for clues of a developing personality. They are quite right to do so, because temperament is a foundation for personality growth. Buttemperament(defined as early-emerging differences in reactivity and self-regulation) is not the whole story. Although temperament is biologically based, it interacts with the influence of experience from the moment of birth (if not before) to shape personality (Rothbart, 2011). Temperamental dispositions are affected, for example, by the support level of parental care. More generally, personality is shaped by thegoodness of fitbetween the child’s temperamental qualities and characteristics of the environment (Chess & Thomas, 1999). For example, an adventurous child whose parents regularly take her on weekend hiking and fishing trips would be a good “fit” to her lifestyle, supporting personality growth. Personality is the result, therefore, of the continuous interplay between biological disposition and experience, as is true for many other aspects of social and personality development.

Personality develops from temperament in other ways (Thompson, Winer, & Goodvin, 2010). As children mature biologically, temperamental characteristics emerge and change over time. A newborn is not capable of much self-control, but as brain-based capacities for self-control advance, temperamental changes in self-regulation become more apparent. For example, a newborn who cries frequently doesn’t necessarily have a grumpy personality; over time, with sufficient parental support and increased sense of security, the child might be less likely to cry.

In addition, personality is made up of many other features besides temperament. Children’s developing self-concept, their motivations to achieve or to socialize, their values and goals, their coping styles, their sense of responsibility and conscientiousness, and many other qualities are encompassed into personality. These qualities are influenced by biological dispositions, but even more by the child’s experiences with others, particularly in close relationships, that guide the growth of individual characteristics.

Indeed, personality development begins with the biological foundations of temperament but becomes increasingly elaborated, extended, and refined over time. The newborn that parents gazed upon thus becomes an adult with a personality of depth and nuance.

Social and Emotional Competence

Social and personality development is built from the social, biological, and representational influences discussed above. These influences result in important developmental outcomes that matter to children, parents, and society: a young adult’s capacity to engage in socially constructive actions (helping, caring, sharing with others), to curb hostile or aggressive impulses, to live according to meaningful moral values, to develop a healthy identity and sense of self, and to develop talents and achieve success in using them. These are some of the developmental outcomes that denote social and emotional competence.

These achievements of social and personality development derive from the interaction of many social, biological, and representational influences. Consider, for example, the development of conscience, which is an early foundation for moral development.Conscienceconsists of the cognitive, emotional, and social influences that cause young children to create and act consistently with internal standards of conduct (Kochanska, 2002). Conscience emerges from young children’s experiences with parents, particularly in the development of a mutually responsive relationship that motivates young children to respond constructively to the parents’ requests and expectations. Biologically based temperament is involved, as some children are temperamentally more capable of motivated self-regulation (a quality calledeffortful control) than are others, while some children are dispositionally more prone to the fear and anxiety that parental disapproval can evoke. Conscience development grows through a good fit between the child’s temperamental qualities and how parents communicate and reinforce behavioral expectations. Moreover, as an illustration of the interaction of genes and experience, one research group found that young children with a particular gene allele (the 5-HTTLPR) were low on measures of conscience development when they had previously experienced unresponsive maternal care, but children with the same allele growing up with responsive care showed strong later performance on conscience measures (Kochanska, Kim, Barry, & Philibert, 2011).

Conscience development also expands as young children begin to represent moral values and think of themselves as moral beings. By the end of the preschool years, for example, young children develop a “moral self” by which they think of themselves as people who want to do the right thing, who feel badly after misbehaving, and who feel uncomfortable when others misbehave. In the development of conscience, young children become more socially and emotionally competent in a manner that provides a foundation for later moral conduct (Thompson, 2012).

Social influences such as cultural norms impact children's interests, dress, style of speech and even life aspirations. [Image: Amanda Westmont, https://goo.gl/ntS5qx, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/Toc0ZF]

Social influences such as cultural norms impact children's interests, dress, style of speech and even life aspirations. [Image: Amanda Westmont, https://goo.gl/ntS5qx, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/Toc0ZF]The development of gender and gender identity is likewise an interaction among social, biological, and representational influences (Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006). Young children learn about gender from parents, peers, and others in society, and develop their own conceptions of the attributes associated with maleness or femaleness (calledgender schemas). They also negotiate biological transitions (such as puberty) that cause their sense of themselves and their sexual identity to mature.

Each of these examples of the growth of social and emotional competence illustrates not only the interaction of social, biological, and representational influences, but also how their development unfolds over an extended period. Early influences are important, but not determinative, because the capabilities required for mature moral conduct, gender identity, and other outcomes continue to develop throughout childhood, adolescence, and even the adult years.

Conclusion

As the preceding sentence suggests, social and personality development continues through adolescence and the adult years, and it is influenced by the same constellation of social, biological, and representational influences discussed for childhood. Changing social relationships and roles, biological maturation and (much later) decline, and how the individual represents experience and the self continue to form the bases for development throughout life. In this respect, when an adult looks forward rather than retrospectively to ask, “what kind of person am I becoming?”—a similarly fascinating, complex, multifaceted interaction of developmental processes lies ahead.

Take a Quiz

Testing yourself regularly is one of the most effective ways to strengthen your learning. Frequent testing helps you identify what you know and don’t know so you can allocate your study time wisely. It also helps you retain information in memory for longer periods of time.

Below you’ll find a 20-item quiz covering the main concepts found in this module. We suggest you start by learning 10 items. When the first session is complete you can either learn the final 10 items in a new session, review items from the first session, or return later.

Cognitive Development in Childhood

ByRobert Siegler

Carnegie Mellon University

This module examines what cognitive development is, major theories about how it occurs, the roles of nature and nurture, whether it is continuous or discontinuous, and how research in the area is being used to improve education.

PDFDownload

Share this URL

Learning Objectives

- Be able to identify and describe the main areas of cognitive development.

- Be able to describe major theories of cognitive development and what distinguishes them.

- Understand how nature and nurture work together to produce cognitive development.

- Understand why cognitive development is sometimes viewed as discontinuous and sometimes as continuous.

- Know some ways in which research on cognitive development is being used to improve education.

Introduction

By the time you reach adulthood you have learned a few things about how the world works. You know, for instance, that you can’t walk through walls or leap into the tops of trees. You know that although you cannot see your car keys they’ve got to be around here someplace. What’s more, you know that if you want to communicate complex ideas like ordering a triple-shot soy vanilla latte with chocolate sprinkles it’s better to use words with meanings attached to them rather than simply gesturing and grunting. People accumulate all this useful knowledge through the process of cognitive development, which involves a multitude of factors, both inherent and learned.

Cognitive development in childhood is about change. From birth to adolescence a young person's mind changes dramatically in many important ways. [Image: One Laptop per Child, https://goo.gl/L1eAsO, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/9uSnqN]

Cognitive development in childhood is about change. From birth to adolescence a young person's mind changes dramatically in many important ways. [Image: One Laptop per Child, https://goo.gl/L1eAsO, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/9uSnqN]Cognitive development refers to the development of thinking across the lifespan. Defining thinking can be problematic, because no clear boundaries separate thinking from other mental activities. Thinking obviously involves the higher mental processes: problem solving, reasoning, creating, conceptualizing, categorizing, remembering, planning, and so on. However, thinking also involves other mental processes that seem more basic and at which even toddlers are skilled—such as perceiving objects and events in the environment, acting skillfully on objects to obtain goals, and understanding and producing language. Yet other areas of human development that involve thinking are not usually associated with cognitive development, because thinking isn’t a prominent feature of them—such as personality and temperament.

As the name suggests, cognitive development is about change. Children’s thinking changes in dramatic and surprising ways. Consider DeVries’s (1969) study of whether young children understand the difference between appearance and reality. To find out, she brought an unusually even-tempered cat named Maynard to a psychology laboratory and allowed the 3- to 6-year-old participants in the study to pet and play with him. DeVries then put a mask of a fierce dog on Maynard’s head, and asked the children what Maynard was. Despite all of the children having identified Maynard previously as a cat, now most 3-year-olds said that he was a dog and claimed that he had a dog’s bones and a dog’s stomach. In contrast, the 6-year-olds weren’t fooled; they had no doubt that Maynard remained a cat. Understanding how children’s thinking changes so dramatically in just a few years is one of the fascinating challenges in studying cognitive development.

There are several main types of theories of child development. Stage theories, such asPiaget’s stage theory, focus on whether children progress through qualitatively different stages of development.Sociocultural theories, such as that of Lev Vygotsky, emphasize how other people and the attitudes, values, and beliefs of the surrounding culture, influence children’s development.Information processing theories, such as that of David Klahr, examine the mental processes that produce thinking at any one time and the transition processes that lead to growth in that thinking.

At the heart of all of these theories, and indeed of all research on cognitive development, are two main questions: (1) How do nature and nurture interact to produce cognitive development? (2) Does cognitive development progress through qualitatively distinct stages? In the remainder of this module, we examine the answers that are emerging regarding these questions, as well as ways in which cognitive developmental research is being used to improve education.

Nature and Nurture

The most basic question about child development is how nature and nurture together shape development.Naturerefers to our biological endowment, the genes we receive from our parents.Nurturerefers to the environments, social as well as physical, that influence our development, everything from the womb in which we develop before birth to the homes in which we grow up, the schools we attend, and the many people with whom we interact.

The nature-nurture issue is often presented as an either-or question: Is our intelligence (for example) due to our genes or to the environments in which we live? In fact, however, every aspect of development is produced by the interaction of genes and environment. At the most basic level, without genes, there would be no child, and without an environment to provide nurture, there also would be no child.

The way in which nature and nurture work together can be seen in findings on visual development. Many people view vision as something that people either are born with or that is purely a matter of biological maturation, but it also depends on the right kind of experience at the right time. For example, development ofdepth perception

,the ability to actively perceive the distance from oneself to objects in the environment, depends on seeing patterned light and having normal brain activity in response to the patterned light, in infancy (Held, 1993). If no patterned light is received, for example when a baby has severe cataracts or blindness that is not surgically corrected until later in development, depth perception remains abnormal even after the surgery.

A child that is perceived to be attractive and calm may receive a different sort of care and attention from adults and as a result enjoy a developmental advantage. [Image: Cairn 111, https://goo.gl/6RpBVt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/HEXbAA]

A child that is perceived to be attractive and calm may receive a different sort of care and attention from adults and as a result enjoy a developmental advantage. [Image: Cairn 111, https://goo.gl/6RpBVt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/HEXbAA]Adding to the complexity of the nature-nurture interaction, children’s genes lead to their eliciting different treatment from other people, which influences their cognitive development. For example, infants’ physical attractiveness and temperament are influenced considerably by their genetic inheritance, but it is also the case that parents provide more sensitive and affectionate care to easygoing and attractive infants than to difficult and less attractive ones, which can contribute to the infants’ later cognitive development (Langlois et al., 1995;van den Boom & Hoeksma, 1994).

Also contributing to the complex interplay of nature and nurture is the role of children in shaping their own cognitive development. From the first days out of the womb, children actively choose to attend more to some things and less to others. For example, even 1-month-olds choose to look at their mother’s face more than at the faces of other women of the same age and general level of attractiveness (Bartrip, Morton, & de Schonen, 2001). Children’s contributions to their own cognitive development grow larger as they grow older (Scarr & McCartney, 1983). When children are young, their parents largely determine their experiences: whether they will attend day care, the children with whom they will have play dates, the books to which they have access, and so on. In contrast, older children and adolescents choose their environments to a larger degree. Their parents’ preferences largely determine how 5-year-olds spend time, but 15-year-olds’ own preferences largely determine when, if ever, they set foot in a library. Children’s choices often have large consequences. To cite one example, the more that children choose to read, the more that their reading improves in future years (Baker, Dreher, & Guthrie, 2000). Thus, the issue is not whether cognitive development is a product of nature or nurture; rather, the issue is how nature and nurture work together to produce cognitive development.

Does Cognitive Development Progress Through Distinct Stages?

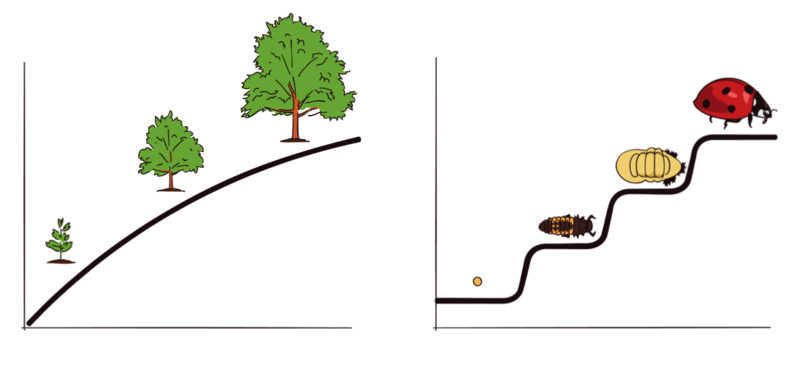

Some aspects of the development of living organisms, such as the growth of the width of a pine tree, involvequantitative changes, with the tree getting a little wider each year. Other changes, such as the life cycle of a ladybug, involvequalitative changes, with the creature becoming a totally different type of entity after a transition than before (Figure 1). The existence of both gradual, quantitative changes and relatively sudden, qualitative changes in the world has led researchers who study cognitive development to ask whether changes in children’s thinking are gradual andcontinuousor sudden anddiscontinuous.

Figure 1: Continuous and discontinuous development. Some researchers see development as a continuous gradual process, much like a maple tree growing steadily in height and cross-sectional area. Other researchers see development as a progression of discontinuous stages, involving rapid discontinuous changes, such as those in the life cycle of a ladybug, separated by longer periods of slow, gradual change.

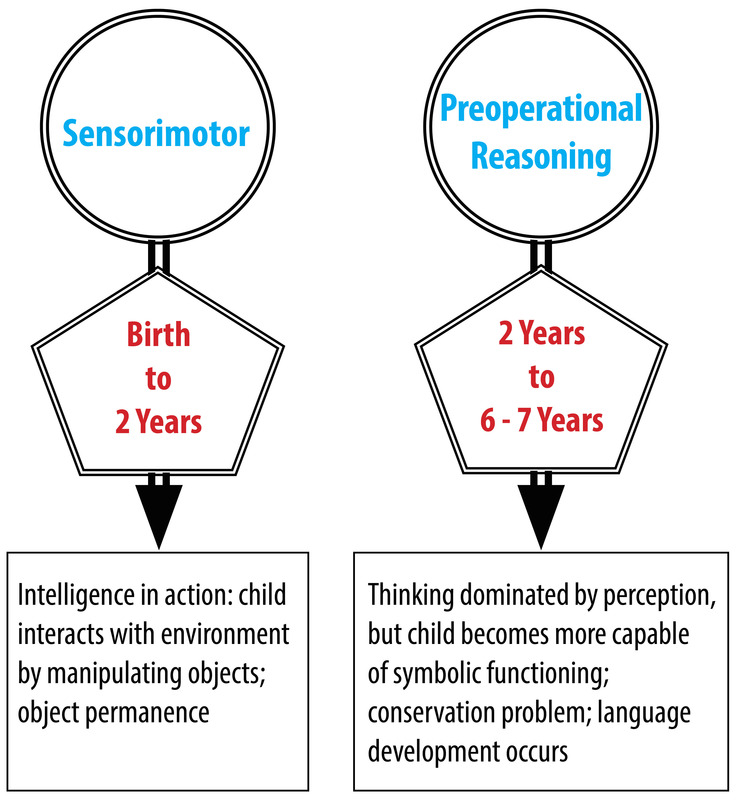

Figure 1: Continuous and discontinuous development. Some researchers see development as a continuous gradual process, much like a maple tree growing steadily in height and cross-sectional area. Other researchers see development as a progression of discontinuous stages, involving rapid discontinuous changes, such as those in the life cycle of a ladybug, separated by longer periods of slow, gradual change.The great Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget proposed that children’s thinking progresses through a series of four discrete stages. By “stages,” he meant periods during which children reasoned similarly about many superficially different problems, with the stages occurring in a fixed order and the thinking within different stages differing in fundamental ways. The four stages that Piaget hypothesized were thesensorimotor stage(birth to 2 years), thepreoperational reasoning stage(2 to 6 or 7 years),theconcrete operational reasoning stage(6 or 7 to 11 or 12 years), and theformal operational reasoning stage(11 or 12 years and throughout the rest of life).

During the sensorimotor stage, children’s thinking is largely realized through their perceptions of the world and their physical interactions with it. Their mental representations are very limited. Consider Piaget’sobject permanence task, which is one of his most famous problems. If an infant younger than 9 months of age is playing with a favorite toy, and another person removes the toy from view, for example by putting it under an opaque cover and not letting the infant immediately reach for it, the infant is very likely to make no effort to retrieve it and to show no emotional distress (Piaget, 1954). This is not due to their being uninterested in the toy or unable to reach for it; if the same toy is put under a clear cover, infants below 9 months readily retrieve it(Munakata, McClelland, Johnson, & Siegler, 1997). Instead, Piaget claimed that infants less than 9 months do not understand that objects continue to exist even when out of sight.

During the preoperational stage, according to Piaget, children can solve not only this simple problem (which they actually can solve after 9 months) but show a wide variety of other symbolic-representation capabilities, such as those involved in drawing and using language. However, such 2- to 7-year-olds tend to focus on a single dimension, even when solving problems would require them to consider multiple dimensions. This is evident in Piaget’s (1952)conservation problems. For example, if a glass of water is poured into a taller, thinner glass, children below age 7 generally say that there now is more water than before. Similarly, if a clay ball is reshaped into a long, thin sausage, they claim that there is now more clay, and if a row of coins is spread out, they claim that there are now more coins. In all cases, the children are focusing on one dimension, while ignoring the changes in other dimensions (for example, the greater width of the glass and the clay ball).

Piaget's Sensorimotor and Pre-operational Reasoning stages

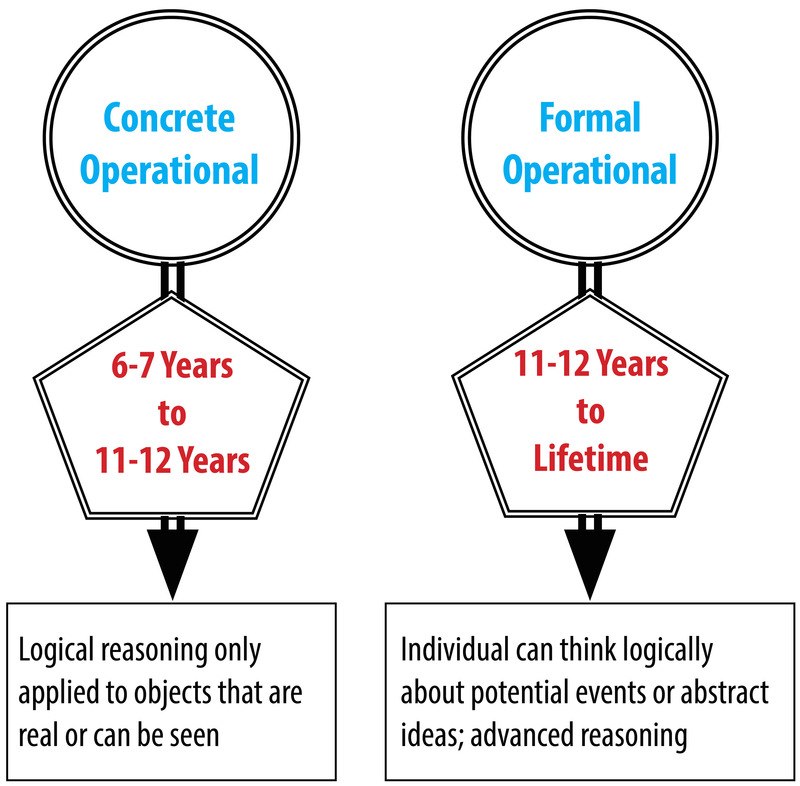

Piaget's Sensorimotor and Pre-operational Reasoning stagesChildren overcome this tendency to focus on a single dimension during theconcrete operations stage, and think logically in most situations. However, according to Piaget, they still cannot think in systematic scientific ways, even when such thinking would be useful. Thus, if asked to find out which variables influence the period that a pendulum takes to complete its arc, and given weights that they can attach to strings in order to do experiments with the pendulum to find out, most children younger than age 12, perform biased experiments from which no conclusion can be drawn, and then conclude that whatever they originally believed is correct. For example, if a boy believed that weight was the only variable that mattered, he might put the heaviest weight on the shortest string and push it the hardest, and then conclude that just as he thought, weight is the only variable that matters (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958).

Finally, in the formal operations period, children attain the reasoning power of mature adults, which allows them to solve the pendulum problem and a wide range of other problems. However, thisformal operations stagetends not to occur without exposure to formal education in scientific reasoning, and appears to be largely or completely absent from some societies that do not provide this type of education.

Although Piaget’s theory has been very influential, it has not gone unchallenged. Many more recent researchers have obtained findings indicating that cognitive development is considerably more continuous than Piaget claimed. For example, Diamond (1985) found that on the object permanence task described above, infants show earlier knowledge if the waiting period is shorter. At age 6 months, they retrieve the hidden object if the wait is no longer than 2 seconds; at 7 months, they retrieve it if the wait is no longer than 4 seconds; and so on. Even earlier, at 3 or 4 months, infants show surprise in the form of longer looking times if objects suddenly appear to vanish with no obvious cause (Baillargeon, 1987). Similarly, children’s specific experiences can greatly influence when developmental changes occur. Children of pottery makers in Mexican villages, for example, know that reshaping clay does not change the amount of clay at much younger ages than children who do not have similar experiences (Price-Williams, Gordon, & Ramirez, 1969).

Piaget's Concrete and Formal Operations stages

Piaget's Concrete and Formal Operations stagesSo, is cognitive development fundamentally continuous or fundamentally discontinuous? A reasonable answer seems to be, “It depends on how you look at it and how often you look.” For example, under relatively facilitative circumstances, infants show early forms of object permanence by 3 or 4 months, and they gradually extend the range of times for which they can remember hidden objects as they grow older. However, on Piaget’s original object permanence task, infants do quite quickly change toward the end of their first year from not reaching for hidden toys to reaching for them, even after they’ve experienced a substantial delay before being allowed to reach. Thus, the debate between those who emphasize discontinuous, stage-like changes in cognitive development and those who emphasize gradual continuous changes remains a lively one.

Applications to Education

Understanding how children think and learn has proven useful for improving education. One example comes from the area of reading. Cognitive developmental research has shown thatphonemic awareness—that is, awareness of the component sounds within words—is a crucial skill in learning to read. To measure awareness of the component sounds within words, researchers ask children to decide whether two words rhyme, to decide whether the words start with the same sound, to identify the component sounds within words, and to indicate what would be left if a given sound were removed from a word. Kindergartners’ performance on these tasks is the strongest predictor of reading achievement in third and fourth grade, even stronger than IQ or social class background (Nation, 2008). Moreover, teaching these skills to randomly chosen 4- and 5-year-olds results in their being better readers years later (National Reading Panel, 2000).

Activities like playing games that involve working with numbers and spatial relationships can give young children a developmental advantage over peers who have less exposure to the same concepts. [Image: Ben Husmann, https://goo.gl/awOXSw, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/9uSnqN]

Activities like playing games that involve working with numbers and spatial relationships can give young children a developmental advantage over peers who have less exposure to the same concepts. [Image: Ben Husmann, https://goo.gl/awOXSw, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/9uSnqN]Another educational application of cognitive developmental research involves the area of mathematics. Even before they enter kindergarten, the mathematical knowledge of children from low-income backgrounds lags far behind that of children from more affluent backgrounds. Ramani and Siegler (2008) hypothesized that this difference is due to the children in middle- and upper-income families engaging more frequently in numerical activities, for example playing numerical board games such asChutes and Ladders. Chutes and Ladders is a game with a number in each square; children start at the number one and spin a spinner or throw a dice to determine how far to move their token. Playing this game seemed likely to teach children about numbers, because in it, larger numbers are associated with greater values on a variety of dimensions. In particular, the higher the number that a child’s token reaches, the greater the distance the token will have traveled from the starting point, the greater the number of physical movements the child will have made in moving the token from one square to another, the greater the number of number-words the child will have said and heard, and the more time will have passed since the beginning of the game. These spatial, kinesthetic, verbal, and time-based cues provide a broad-based, multisensory foundation for knowledge ofnumerical magnitudes(the sizes of numbers), a type of knowledge that is closely related to mathematics achievement test scores (Booth & Siegler, 2006).

Playing this numerical board game for roughly 1 hour, distributed over a 2-week period, improved low-income children’s knowledge of numerical magnitudes, ability to read printed numbers, and skill at learning novel arithmetic problems. The gains lasted for months after the game-playing experience (Ramani & Siegler, 2008; Siegler & Ramani, 2009). An advantage of this type of educational intervention is that it has minimal if any cost—a parent could just draw a game on a piece of paper.

Understanding of cognitive development is advancing on many different fronts. One exciting area is linking changes in brain activity to changes in children’s thinking (Nelson et al., 2006). Although many people believe that brain maturation is something that occurs before birth, the brain actually continues to change in large ways for many years thereafter. For example, a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, which is located at the front of the brain and is particularly involved with planning and flexible problem solving, continues to develop throughout adolescence (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006). Such new research domains, as well as enduring issues such as nature and nurture, continuity and discontinuity, and how to apply cognitive development research to education, insure that cognitive development will continue to be an exciting area of research in the coming years.

Conclusion

Research into cognitive development has shown us that minds don’t just form according to a uniform blueprint or innate intellect, but through a combination of influencing factors. For instance, if we want our kids to have a strong grasp of language we could concentrate on phonemic awareness early on. If we want them to be good at math and science we could engage them in numerical games and activities early on. Perhaps most importantly, we no longer think of brains as empty vessels waiting to be filled up with knowledge but as adaptable organs that develop all the way through early adulthood.